Amber is the name given to over 100 types of fossilized resin.

Number of products : 336Amber is the name given to over 100 types of fossilized resin that have been discovered around the world to date.Fossil resins with a documented origin are given their own mineralogical names, e.g. cedaryte, gedanite, glessite, rumenite, succinite, stantienite.

Succinite occupies a special place among fossil resins. It is the earliest and best known type of amber. Already in ancient times, it was believed that “amber is tree juice (succus)” and was called “succinum.” The name “succinite” was introduced into mineralogical lists in 1820 by August Breithaupt.

Regional names for succinite are also used, related to its occurrence in Central Europe. The name “Baltic amber” is commonly used, while amber of similar origin found in Ukraine is also called Ukrainian amber, and amber found in central and eastern Germany is known as Bitterfeld amber (after the town of Bitterfeld in Saxony).

The history of Baltic amber

Baltic amber was formed from the transformed resin of coniferous trees that grew in the Middle Paleogene period, approximately 40 million years ago, on the northern and eastern coasts of the epicontinental sea that filled the eastern part of the North Sea basin. The resin from amber trees was transported to the sea by a river network and surface runoff, and underwent advanced diagenesis, primarily polymerization, in the marine environment.

These processes led to changes in the physicochemical properties of the resin, including an increase in hardness and melting point, and consequently to the formation of the substance known today as Baltic amber. Amber fragments were transported by sea currents and deposited among fine-grained clastic sediments: sands, silts, and glauconite-quartz clays. Such sediments in their classic location – on the Sambian Peninsula – are called “blue earth.”

The formation of amber

About 30–40 million years ago, a significant part of today's Polish territory and the neighboring areas were covered by a shallow sea. Vast tracts of land were covered with forests. The forest communities of the higher parts of the mountains were home to redwoods, firs, spruces, pines, larches, cypresses, cedars, and thujas. The lower parts were covered with pine and palm forest steppe, while the river valleys were home to moist forests with wax myrtles and willows. Among the trees were highly resinous, amber-producing species. The resin of the trees accumulated directly under the bark and inside the trunks, filling the layers of wood and cracks. The resin that leaked onto the surface of the trunks solidified in the form of drops and icicles. It formed swellings that regenerated damaged tissue and sealed exposed wounds. Small pieces of bark, needles, leaves, and debris from the forest floor were carried into the resinous substance flowing down the trunks. The liquid, sticky resin was also a trap for animals. Small arthropods – insects, arachnids, and worms, and sometimes larger animals such as lizards – found their end in the amber resin. These organic inclusions in amber are still evidence of the rich world of plants and animals in that distant geological era.

Large amounts of resin stuck in fallen tree trunks seeped into the ground, forming primary deposits. Over time, the deposits eroded – heavy rains washed away the soil and carried lumps of solidified resin to nearby streams. The resinous material was transported and deposited in the shallow coastal zone of the Eocene Sea, transforming into Baltic amber. In subsequent geological eras, amber continued its journey to new places. All amber accumulations preceded by more or less distant transport belong to secondary deposits of sedimentary origin.

Amber occurs in large areas of Central Europe in the form of primary deposits associated with Middle and Upper Eocene sediments and secondary deposits associated with younger, mainly Quaternary sediments. There are three main types of amber deposits:

-

stratoidal-bed deposits occurring in Paleogene formations (primary deposits),

-

stratoids, nest-lens-shaped, forming amber accumulations in Holocene, coastal-marine and alluvial formations (secondary deposits),

-

nest-shaped, occurring among Pleistocene formations, mainly in amber-bearing rifts of Paleogene formations and in sandur areas (secondary deposits).

In Poland, amber occurs not only in the coastal zone, but also in areas far from the Baltic Sea. Primary accumulations in Poland have been found quite commonly. The most significant accumulations are found on the Kashubian Coast (Chłapowo region) and in northern Lublin, where Eocene deposits occur relatively shallow. In both regions, amber accumulations are of a deposit nature. In the vicinity of the Polish border, known amber deposits occur on the Sambij Peninsula in Russia and in Volhynia (Ukraine).

There are also secondary amber accumulations in the Baltic coastal region. These small accumulations are often small deposits, but are usually exploited at the discovery stage. The most important are the deposit-type amber accumulations found in the northern part of the Lublin region. Amber occurs here as a mineral accompanying sand and glauconite silt. These deposits are located near or are part of the previously documented Górka Lubartowska deposit.

According to archaeological data, the history of Baltic amber extraction and processing dates back to the third millennium BC. Initially, amber was fished out of the sea, although it was probably also dug out of shallow layers of soil. Amber mining began to develop in the 18th century.

Within the present-day borders of Poland, over 750 sites where Baltic amber was found or mined have been inventoried. The rapid development of amber mining took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In numerous shaft mines. Some of the mines survived until the beginning of the 20th century. Several mines existed in the traditional area of the Vistula Spit and the Vistula Delta. The succinite deposits found here are still the main source of large quantities of amber.

Between 1860 and 1890, the bottom of the Curonian Lagoon was also dredged using steam-powered steel dredgers. As a result of geological research conducted in the mid-19th century, large quantities of amber were discovered on the Sambij Peninsula and named “blue earth” (Blaue Erde). Open-pit mines began to appear on the cliff-lined shores of the peninsula. From the mid-19th century to the 1920s, deep mines operated on the east coast, and in 1874, the first modern open-pit mine on land was opened.

Natural amber - extraction methods

Natural amber is extracted from deposits using various methods depending on the type of deposit. Amber from stratiform Paleogene deposits is mined using the open-pit method. The amber mine initially crushes the extracted material with a strong stream of water fed by hydromonitors and hydraulically transported through a pipeline system to a sorting plant located outside the excavation site.

In Poland, the deposit discovered in the Górka Lubartowska – Niedźwiady area in the Lublin region is exploited using the hydraulic open-pit method. This involves creating funnels from the surface of the ground using a stream of water that washes away the excavated soil. The water stream is fed into the soil through a flexible hose with a head, which is manually lowered using a rod.

In 2012, the open-pit method was used for the first time for mining in Gdańsk. The waterlogged material from the bottom of the excavation was transported by a conveyor belt to screens, where the amber was separated from the base mineral (sand).

Nest deposits were exploited on a large scale in the 19th century. Amber mines were located in Western and Eastern Pomerania. So-called box mines were commonly used. These were shafts lined with thick frames and platforms stacked one above the other to facilitate the transfer of the excavated material to the top of the excavation. The depth of the shafts usually reached several meters. The deepest mine known from the Ugoszczy area near Bytów was 27 m deep.

Baltic amber was also extracted from the bottom of water bodies. In the second half of the 19th century, the bottom of the Curonian Lagoon was penetrated with steam-powered steel dredgers. In Poland, attempts to search for amber in the coastal waters of the Gulf of Gdańsk were made in the 1970s and at the beginning of the 21st century. The work involved the use of a suction dredger connected by a pipeline to a pontoon, on which there was a set of sieves for separating amber nuggets from the sediment. The sediment was sent to a previous excavation site for disposal.

Traditionally, Jantar is fished from the sea off the coast of the Vistula Spit, especially during stormy periods. As in centuries past, special nets attached to long poles, known as kaszorki, are used to catch the lumps.

Baltic amber is a mineraloid of organic origin. It is characterized by low hardness of 2–2.5 on the Mohs scale and low density (0.9–1.1 g/cm3), similar to that of water. It has electrostatic properties. When rubbed, it becomes negatively charged, attracting small, light particles (e.g., paper). When rubbed vigorously or heated, it gives off a pleasant resinous odor. It burns with a bright, sooty flame, hence its German name Bernstein – a stone that burns. Amber is described by the general formula C10H16O. The individual elements occur in varying percentages: 61–81% is carbon, 8.5–11% is hydrogen, and the remainder is oxygen.

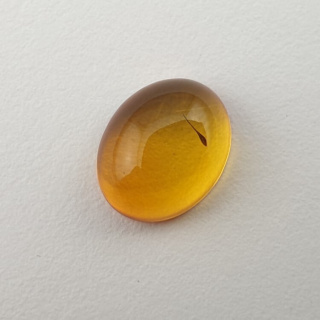

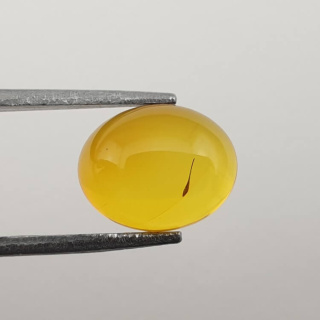

A special feature that distinguishes amber from other fossil resins is its succinic acid content of 3 to 8%. This acid has not been found in other fossil resins, or only in quantities below 3%. In addition, Baltic amber is characterized by a variety of types not found in other resins, resulting from differences in transparency and color. It is usually yellowish in color, in various shades. It can also be milky white, reddish or brownish, and less commonly bluish or greenish. Depending on the amount of gas bubbles it contains, it can be transparent, translucent or cloudy.

Baltic amber contains the remains of ancient plants and animals, especially various species of flies, ants, beetles, as well as leaves and stems of plants, forming so-called inclusions. These allow the natural environment in which it was formed to be determined. A unique inclusion in a piece of Baltic amber is a lizard specimen found in Gdańsk-Stogi, currently on display at the Amber Museum in Gdańsk.

Primary varieties of amber

Among the primary varieties of amber, transparent amber (1) stands out, in which there are no gas bubbles (so-called cacko, honey amber) or with a small amount of gas bubbles (with a cloud), and translucent amber (cloudy or woolly), where large gas bubbles cause local cloudiness.

If the number of gas bubbles visible under an electron microscope reaches 25,000 per 1 mm², opaque yellow amber is formed, with a whole range of yellows and beiges, sometimes with the addition of white. Thanks to the different color patterns, it is possible to distinguish mottled, marbled, and mosaic amber, as well as striped and layered amber, and cabbage amber, in which light streaks on a yellow background resemble the veins of a cabbage leaf. Opaque white amber is formed when the number of gas bubbles reaches 900,000 per 1 mm². The internal structure then takes on a foamy character, the amber is very light and its color becomes white. Among this variety, chalk amber stands out – chalk-white in color and light, white with a brownish bone shade, as well as unique bluish amber.

Amber, regardless of its internal bubble structure, can be contaminated to varying degrees, in which case it is referred to as “earth amber.” This variety is brown or greenish in color and contains fine plant detritus, wood chips, and sometimes animal and plant inclusions. The “earthy” variety includes, among others, rowan amber, in which gray or black particles of plant detritus stand out against a yellow background.

Secondary varieties of amber

Exposure to air, light, and changes in humidity and temperature affect the color and structure of primary varieties of amber. Secondary varieties are formed. The yellow color changes to orange or red, forming red amber (6) or fire amber. Multidirectional cracks form, changing the structure of the amber to a sugary texture. The weathered surface of the nuggets becomes rough and uneven, and the amber is covered with a characteristic “bark.”

Baltic amber – the use of amber in industry, art and esotericism

Amber has been attributed with magical and healing properties for centuries. The first information about its beneficial effects can be found in the writings of Hippocrates and Pliny the Elder. Due to the characteristic smell emitted when amber is burned, it was used as incense during religious ceremonies in ancient Greece.

Since ancient times, however, Baltic amber has been used mainly for the production of luxurious decorations and luxury items. Amber jewelry became very popular – original and technically advanced necklaces were found across a large area, from the Rhine to the Black Sea. Many processing centers existed on the Gulf of Gdańsk and in the Vistula River Delta. The establishment of a guild statute in 1477 by the Gdańsk Council, and soon afterwards by the authorities of Elbląg, contributed to the lasting economic and cultural development of the amber-working community in the Gdańsk Bay area. Thanks to the requirements imposed on master amber craftsmen, richly decorated larger objects began to appear, such as altars, caskets and cabinets, which were sought after by courts throughout Europe. Gdańsk masters were famous for this art.

Amber is still the most famous and widespread gemstone in Poland, and Polish amber craftsmanship is distinguished by the individual character of its products. Amber jewelry most often combines amber with silver. In larger works, the qualities of unique varieties of colored succinite are brought out. Gdańsk, together with other Polish succinite processing centers, remains the world leader in original amber jewelry and artistic products. It is estimated that between 60 and 150 tons of raw material are used annually in Poland for the production of amber jewelry.

Amber is also used in the manufacture of paints, polishes and pigments. The succinic acid it contains can be used as a raw material in the production of plastics such as polybutylene succinate (PBS) and polyurethanes, solvents and plasticizers.

The use of amber in alternative medicine, pharmacy, and cosmetics is also very common. It has antibacterial and antiseptic properties. Amber ointment is made from it – the terpenes it contains have a warming effect and help treat rheumatic pain. Amber spirit tincture is believed to strengthen immunity, relieve symptoms of colds, runny nose, fever, rheumatic pains, and muscle aches.

Amber - interesting facts

The largest piece of Baltic amber is about 50 cm long and weighs 9.75 kg. It was found at the beginning of the 20th century in Rarwin near Kamień Pomorski. It is currently on display at the Natural History Museum of Humboldt University in Berlin.

The Amber Mountain in Bąkowo near Gdańsk – one of the few visible traces of former amber mining in the area – is now a geosite and archaeological reserve. The mine was most likely in operation from the 18th to the early 20th century.

The Amber Trail is the name of a trade route between European countries in the Mediterranean basin and the lands on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea. The object of trade was amber. The first organized expeditions for this raw material took place in the 5th century BC, but they did not reach the Baltic coast, and amber was purchased from Celtic intermediaries. The peak of trade on this route was in the 5th century AD.

One of the most famous works of art was the Amber Room, commissioned from Gdańsk masters in the early 18th century by Frederick I for his palace in Charlottenburg near Berlin. In 1716, Tsar Peter I received it as a gift from Frederick William as a token of friendship. It was installed in the palace in Tsarskoye Selo near St. Petersburg, from where it was stolen by the Germans in 1941. It has not been found to this day.

The greatest contemporary work of Gdańsk's master craftsmen is the Amber Altar in St. Bridget's Basilica in Gdańsk, which, according to the original design, is to cover over 100 m2 with amber. The altar is half finished, but thanks to the architectural concept of its creators, the work gives the impression of being complete at every stage of construction.The Polish A1 motorway has been named the Amber Motorway (Amber One). It is part of the international E75 route. This motorway is the only Polish motorway running along a meridian.In the 16th century, the Vistula Spit was called Ripa Succini – the amber coast.

![[{[item.product.name]}]]([{[item.product.photo.url]}] 75w)